D’après : Policy statement. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. American Academy of Pediatrics. Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ. Pediatrics 2012 ; 129(3) : e827-41.

Six années se sont écoulées depuis les dernières recommandations de l’AAP sur l’allaitement. Les données récentes ont confirmé que le lait humain était la référence pour l’alimentation du petit de notre espèce. Suite aux nouvelles données disponibles, l’Académie Américaine de Pédiatrie réaffirme sa recommandation d’un allaitement exclusif d’environ 6 mois, suivi par la continuation de l’allaitement lorsque des aliments de complément sont introduits, et la poursuite de l’allaitement durant un an ou plus longtemps selon les souhaits de la mère et de l’enfant.

Dans les pays industrialisés, le taux de démarrage de l’allaitement est très variable suivant les pays. Aux États-Unis, il est de 75 % d’après les plus récentes statistiques nationales. Dans les pays européens où ces données sont disponibles, le taux d'allaitement exclusif chez les bébés âgés de 3 mois va d’environ 16 % en Italie à 97 % en Hongrie.

Par ailleurs, même si la durée de l’allaitement a augmenté dans de nombreux pays industrialisés, elle reste très inférieure à ce qui est recommandé par l’OMS. Dans les pays en voie de développement, si l’allaitement est la norme, très peu de bébés sont exclusivement allaités pendant les 6 premiers mois. Partout, de nombreux nouveau-nés reçoivent des suppléments de formule lactée commerciale pendant les premières 48 heures post-partum, voire même divers produits avant la première mise au sein.

Santé infantile…

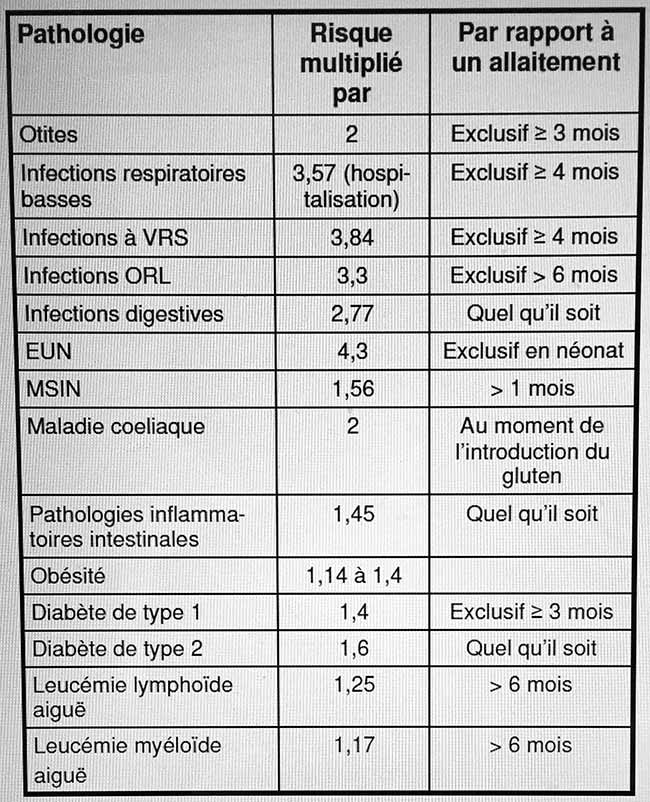

Le mode d’alimentation choisi par la mère aura un impact sur la santé de l’enfant, mais également sur celle de la mère, y compris dans les pays industrialisés. Malheureusement, de nombreuses études sur cet impact souffrent de biais méthodologiques variés (données incomplètes sur les pratiques d’allaitement, mauvaise prise en compte des variables confondantes…). Et la majorité des études sont observationnelles. D’après les données actuelles les plus fiables, on peut estimer que le risque d’hospitalisation pour infection respiratoire basse est 3,57 fois plus élevé et les infections sévères à virus respiratoire syncytial 3,84 fois plus fréquentes chez les enfants non allaités ou partiellement allaités par rapport aux enfants exclusivement allaités pendant > 4 mois. Par rapport aux enfants exclusivement allaités pendant ≥ 3 mois,le risque d’otite est 2 fois plus élevé chez les enfants non allaités. Leur risque d’infections ORL est 3,3 fois plus élevé par rapport aux enfants exclusivement allaités pendant 6 mois. Le non-allaitement est corrélé à un risque 2,77 fois plus élevé d’infection du tractus digestif. Par rapport aux enfants qui recevaient du lait humain, le risque d’entérocolite ulcéronécrosante (EUN) était 2,3 fois plus élevé chez ceux qui n’en recevaient pas, et une étude plus récente a même retrouvé chez ces derniers un risque 4,3 fois plus élevé d’EUN par rapport aux prématurés nourris exclusivement avec du lait humain (lait maternel et/ou lait humain provenant de donneuses). Par rapport à un allaitement de > 1 mois,le non-allaitement est corrélé à un risque 1,56 fois plus élevé de mort subite inattendue du nourrisson (MSIN) ; cet impact, indépendant de la position de sommeil, est encore plus important en cas d’allaitement exclusif. On peut estimer que 21 % de la mortalité infantile aux États-Unis serait liée en partie à l’augmentation du risque de MSIN liée au non-allaitement. On a également calculé que plus de 900 décès de nourrissons pourraient être évités tous les ans dans ce pays si 90 % des mères allaitaient exclusivement pendant 6 mois.Dans les pays en voie de développement où surviennent 90 % des décès chez les jeunes enfants, le respect des recommandations internationales sur l’allaitement serait l’intervention la plus efficace pour abaisser la mortalité infantile, en évitant plus d’un million de décès tous les ans. Une analyse détaillée des coûts de santé pédiatrique concluait que si 90 % des mères américaines allaitaient exclusivement jusqu’à 6 mois, cela permettrait d’économiser tous les ans 13 milliards de dollars ; cette estimation est prudente, dans la mesure où on n’a pas pris en compte le coût de l’absentéisme parental pour s’occuper de l’enfant malade, ou le coût des traitements au long cours des pathologies chroniques.

L’allaitement est particulièrement bénéfique pour les prématurés : risque plus bas d’entérocolite ulcéronécrosante (et des séquelles liées à cette pathologie sévère), meilleur développement neurologique, risque plus bas d’hospitalisation pendant la première année, risque plus bas de rétinopathie sévère… Tous les prématurés devraient être nourris avec du lait humain, soit du lait maternel exprimé, soit du lait provenant de donneuses, enrichi si nécessaire. À noter que le lait maternel cru peut être stocké dans le réfrigérateur du service de néonatalogie à 4°C pendant 96 heures.

Augmentation du risque de certaines pathologies chez les enfants non allaités par rapport aux enfants allaités

.… et santé maternelle

L’allaitement présente également des bénéfices pour la mère, à court et à long terme. La perte de sang en post-partum est moins importante, et l’involution de l’utérus est plus rapide. L’aménorrhée de la lactation permet un espacement naturel des naissances. Le risque de dépression est plus élevé chez les femmes qui n’allaitent pas ou qui sèvrent rapidement. Une étude faisait état d’un risque 2,6 fois plus élevé de maltraitance ou de négligence chez les enfants non allaités. Il semble que l'allaitement exclusif long favorise la perte de poids chez la mère, mais les données actuelles ne permettent pas de conclure en raison de nombreuses variables confondantes. L’absence d’allaitement augmente le risque maternel de survenue d’un diabète de type 2 (risque 1,35 fois plus élevé par rapport aux femmes ayant allaité pendant 12 à 23 mois), de polyarthrite rhumatoïde (risque 2 fois plus élevé par rapport aux femmes qui ont allaité pendant > 2 ans), et de pathologies cardiovasculaires. Par rapport à une durée totale d’allaitement > 12 mois, le non-allaitement est corrélé à un risque 1,38 fois plus élevé de cancer du sein et des ovaires, chaque année supplémentaire d’allaitement étant corrélée à une réduction supplémentaire de 4,3 % de ce risque.

Pathologies allergiques et obésité

Les données concernant l’impact de l’allaitement sur l’allergie sont conflictuelles. Il semble que l’allaitement abaisse le risque d’asthme, de dermatite atopique et d’eczéma de 27 % dans une population à bas risque, et de 42 % chez les enfants ayant de antécédents familiaux d’allergie. Un des problèmes pour l’évaluation de l’impact de l’allaitement exclusif est le faible pourcentage d’enfants exclusivement allaités jusqu’à 6 mois. Le risque de maladie coeliaque est 2 fois plus élevé chez les enfants qui ne sont plus allaités au moment de l’introduction du gluten. Ce dernier devrait être introduit alors que l’enfant ne reçoit pas de lait de vache ni de formule lactée commerciale. Le non allaitement est corrélé à un risque 1,45 fois plus élevé de pathologie intestinale inflammatoire.

Bien qu’il soit difficile d’avancer des chiffres fiables en la matière au vu des nombreuses variables confondantes, il semble que le non-allaitement est corrélé à un risque d’obésité à l’adolescence et à l’âge adulte 1,14 à 1,4 fois plus élevé, cette corrélation étant dose-dépendante. Par rapport à un allaitement exclusif de ≥ 3 mois, le non-allaitementest corrélé à un risque de diabète 1,4 fois plus élevé. On a constaté un taux de leucémie lymphoïde aiguë et de leucémie myéloïde aiguë respectivement 1,25 et 1,17 fois plusélevé chez les enfants non allaités par rapport aux enfants allaités pendant ≥ 6 mois, cet impact étant plus faible en cas d’allaitement plus court. Il existe de très nombreuses variables confondantes rendant difficile d’évaluer l’impact de l’allaitement sur le développement neurologique et cognitif. Toutefois, il semble que ce développement est meilleur chez les enfants exclusivement allaités pendant ≥ 3 mois, en particulier chez les prématurés.

Contre-indications à l’allaitement

Il existe peu de contre-indications à l’allaitement. En cas de galactosémie classique, l’enfant devra recevoir une formule lactée commerciale spéciale. En cas de phénylcétonurie, il pourra habituellement être partiellement allaité avec un suivi adéquat. Les mères souffrant de brucellose non traitée ou de HTLV-1 ne devraient pas allaiter. L’allaitement devrait être suspendu si la mère souffre de tuberculose active, ou présente des lésions d’herpès sur les seins, mais elle peut tirer son lait pour qu’il soit donné à son bébé. La mère qui déclare une varicelle dans les 5 jours précédant l’accouchement et les 2 premiers jours post-partum sera séparée de son bébé, mais celui-ci pourra recevoir du lait maternel exprimé. Dans les pays industrialisés, on déconseille l’allaitement chez les mères séropositives pour le VIH, tandis que les bénéfices de l’allaitement pourront être plus élevés que les risques liés au VIH dans les pays en voie de développement. L’allaitement exclusif abaisse le risque de transmission verticale du VIH. Lorsque l’enfant est né à terme, le fait que la mère soit séropositive pour le CMV ne pose aucun problème, mais cela pourra induire une infection chez les enfants de très petit poids de naissance (< 1 500 g /32 semaines à la naissance). Toutefois, la faiblesse du risque lié au CMV n’empêche pas de recommander le don de lait maternel cru en routine à tous les prématurés. La toxicomanie maternelle n’est pas une contre-indication formelle à l’allaitement ; les mères seront conseillées au cas par cas. La consommation d’alcool devrait être limitée à 0,5 g d’alcool / kg, et être occasionnelle ; attendre 2 heures après la consommation d’alcool pour mettre l’enfant au sein. Le tabagisme ne contre-indique pas l’allaitement, mais on recommandera à la mère de limiter son tabagisme, et d’éviter d’exposer son enfant au tabagisme passif.

Alimentation de la mère allaitante

Il n’existe pas de recommandations spécifiques concernant l’alimentation de la mère allaitante. De nombreux spécialistes conseillent de poursuivre la prise des suppléments vitaminiques recommandés pendant la grossesse. L’alimentation maternelle devrait apporter 200 à 300 mg/jour d’acides gras à longue chaîne en oméga-3, par le biais d’une à deux portions de poisson par semaine, en limitant la consommation des poissons de fin de chaîne alimentaire (préférer des poissons tels que sardines, maquereau…). Lorsque la mère doit prendre des médicaments, le risque lié à l’excrétion lactée des médicaments sera comparé aux bénéfices de la poursuite de l’allaitement. Peu de médicaments sont contre-indiqués chez la mère allaitante, et on pourra habituellement prescrire d’autres produits. On choisira de préférence les produits pour lesquels il existe des données. Il existe des sources fiables sur la compatibilité des médicaments avec l’allaitement (LactMed par exemple). La US Nuclear Regulatory Commisson a publié des recommandations sur l’utilisation des produits de radiodiagnostic pendant l'allaitement. Le fait que l’enfant souffre d’un déficit en G6PD amènera à déconseiller davantage de médicaments.

Pratiques en maternité

En 2009, l’AAP a reconnu que le respect des 10 Conditions de l’OMS/UNICEF par les services de maternité permettait d’augmenter la prévalence et la durée del’allaitement, y compris celles de l’allaitement exclusif. Les pratiques qui s’avèrent les plus efficaces pour augmenter la durée de l’allaitement sont une première mise au sein dans l’heure qui suit la naissance, l’allaitement exclusif et la cohabitation mère-enfant 24 heures sur 24 pendant le séjour en maternité, le fait de ne pas donner de sucette, et le fait de donner aux mères les coordonnées de personnes qui pourront les soutenir après leur sortie de maternité. Or, une enquête menée auprès des services de maternité américains a montré un score moyen de mise en œuvre des 10 Conditions de seulement 65 %. 41 % des services distribuaient des sucettes aux bébés, et dans 58 % on recommandait aux mères de limiter la durée des tétées. De nombreux nouveau-nés reçoivent des suppléments de formule lactée commerciale. 66 % des services distribuaient aux mères des paquets cadeau contenant du lait industriel. Seulement 37 % des services mettaient en œuvre 5 des 10 Conditions, et seulement 3,5 % mettaient en œuvre 9 des 10 Conditions. Il est nécessaire de modifier l’organisation des services afin qu’elle respecte davantage les besoins des mères et des bébés. La formation des équipes soignantes passe par l’amélioration de leurs connaissances sur l’allaitement, mais aussi par la nécessité de modifier les attitudes, et de cesser de croire que les formules lactées commerciales sont plus ou moins équivalentes au lait maternel. Les sucettes devraient être réservées à des situations spécifiques, comme analgésique et calmant, ou dans le cadre d’un programme pour améliorer la fonction orale, ou encore pendant les périodes de sommeil de l’enfant après 3-4 semaines post-partum. De la vitamine K1 (0,5 à 1 mg) devrait être injectée à tous les nouveau-nés pour la prévention de l’hémorragie du postpartum. On devrait attendre la fin de la première tétée, mais cette injection devrait être faite avant 6 heures de vie. Tous les nourrissons devraient recevoir 400 UI/jour de vitamine D dès leur sortie de maternité (NDLR : les pratiques américaines diffèrent des pratiques françaises). Les enfants de moins de 6 mois ne devraient pas recevoir de fluor. Par la suite, du fluor pourra être donné uniquement aux enfants vivant dans des régions où le taux de fluor dans l’eau du robinet est < 0,3 ppm. Des aliments riches en fer et en zinc devraient être introduits à partir de 6 mois. Les prématurés devraient recevoir des compléments vitaminiques et minéraux jusqu’à ce qu’ils soient totalement diversifiés. Le suivi de la croissance de tous les enfants jusqu’à 24 mois devrait être effectué à partir des courbes établies par l’OMS, qui ont été établies à parti rd’enfants allaités et qui reflètent ce que devrait être la croissance optimale des enfants.

Rôle des professionnels de santé

Les pédiatres ont un rôle majeur à jouer auprès de leurs patients, de leur communauté et de la société, en tant qu’avocats et supporters de l’allaitement. Or, des études ont montré qu’ils n’étaient pas suffisamment formés en matière d’allaitement. Le site de l’AAP offre diverses ressources pour soutenir les pédiatres dans leur rôle auprès des mères allaitantes. Les protocoles de l’Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine sont également une bonne source d’information. Le fait que le lieu de travail soit « Ami de l’allaitement » présente des avantages pour les employeurs : absentéisme moindre des employées, plus grande satisfaction de celles-ci,ce qui améliorera leur productivité. Investir dans des mesures qui permettront aux mères de poursuivre l’allaitement pourra faire économiser de l’argent à l'employeur. Les services de santé américains ont créé un programme destiné aux employeurs, décrivant les bénéfices pour eux de la poursuite de l’allaitement chez leurs employées, et leur proposent des outils et des stratégies pour rendre leur entreprise Amie de l’allaitement.

En conclusion

L’AAP recommande l’allaitement exclusif pendant les 6 premiers mois. Cette recommandation se fonde sur la constatation de différences en matière de santé infantile entre lesenfants allaités exclusivement pendant 4 mois, et ceux l’étant pendant 6 mois, ainsi que des différences sur la santé maternelle. L’AAP constate que certains enfants reçoivent d’autres aliments avant 6 mois pour diverses raisons, et recommande la poursuite de l’allaitement pendant la première année, parallèlement à l’introduction d’une alimentation variée. Étant donné ses implications en matière de santé publique, l’allaitement ne devrait pas être regardé comme un choix personnel, mais comme une importante question de santé publique. Les pédiatres ont un rôle majeur à jouer en encourageant activement l’allaitement, en informant les mères sur les pratiques optimales d’allaitement, afin d’améliorer les statistiques actuelles.

Références

1. Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al., American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):496-506

2. Schanler RJ, Dooley S, Gartner LM, Krebs NF, Mass SB. Breastfeeding Handbook for Physicians. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2006

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Sample Hospital Breastfeeding Policy for Newborns. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008

4. Feldman-Winter L, Barone L, Milcarek B, et al. Residency curriculum improves breastfeeding care. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):289-297

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Safe and Health Beginnings: A Resource Toolkit for Hospitals and Physicians’ Offices. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Among U.S. Children Born 1999–2006, CDC National Immunization Survey. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010

7. McDowell MM, Wang C-Y, Kennedy-Stephenson J. Breastfeeding in the United States: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999–2006. NCHS Data Briefs, no. 5. Hyatsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008

8. 2007 CDC National Survey of Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009

9. Healthy People 2010.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding report card—United States, 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm

11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Maternal, infant, and child health. Healthy People 2020; 2010. Available at: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=26

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(11):327-334

13. Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al., Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-based Practice Center. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007;153(153):1-186

14. Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s evidence report on breastfeeding in developed countries. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(suppl 1):S17-S30

15. Chantry CJ, Howard CR, Auinger P. Full breastfeeding duration and associated decrease in respiratory tract infection in US children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):425-432

16. Nishimura T, Suzue J, Kaji H. Breastfeeding reduces the severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection among young infants: a multi-center prospective study. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(6):812-816

17. Duijts L, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Moll HA. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in infancy. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/126/1/e18

18. Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4).

19. Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, et al. An exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk-based products. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):562–567, e1pmid:20036378

20. Hauck FR, Thompson JMD, Tanabe KO, Moon RY, Vennemann MM. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):1-8

21. Chen A, Rogan WJ. Breastfeeding and the risk of postneonatal death in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/113/5/e435

22. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1030-1039

23. Vennemann MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, et al., GeSID Study Group. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics. 2009;123(3).

24. Bartick M, Reinhold A. The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: a pediatric cost analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5).

25. Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362(9377):65-71

26. Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183-191

27. Zutavern A, Brockow I, Schaaf B, et al., LISA Study Group. Timing of solid food introduction in relation to atopic dermatitis and atopic sensitization: results from a prospective birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):401-41

28. Poole JA, Barriga K, Leung DYM, et al. Timing of initial exposure to cereal grains and the risk of wheat allergy. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2175-218

29. Zutavern A, Brockow I, Schaaf B, et al., LISA Study Group. Timing of solid food introduction in relation to eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food and inhalant sensitization at the age of 6 years: results from the prospective birth cohort study LISA. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1).

30. Nwaru BI, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, et al. Age at the introduction of solid foods during the first year and allergic sensitization at age 5 years. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):50-59

31. Akobeng AK, Ramanan AV, Buchan I, Heller RF. Effect of breast feeding on risk of coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(1):39-43

32. Barclay AR, Russell RK, Wilson ML, Gilmour WH, Satsangi J, Wilson DC. Systematic review: the role of breastfeeding in the development of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 2009;155(3):421-426

33. Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):511-521

34. Perrine CG, Shealy KM, Scanlon KS, et al., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: hospital practices to support breastfeeding—United States, 2007 and 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(30):1020-1025

35. U.S.Department of Health and Human Services, The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/breastfeeding/

36. Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1367-1377

37. Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Ingelsson E, et al. Breastfeeding in infancy and adult cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):656-663, e1

38. Metzger MW, McDade TW. Breastfeeding as obesity prevention in the United States: a sibling difference model. Am J Hum Biol. 2010;22(3):291-296

39. Dewey KG, Lönnerdal B. Infant self-regulation of breast milk intake. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1986;75(6):893-898

40. Li R, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Association of breastfeeding intensity and bottle-emptying behaviors at early infancy with infants’ risk for excess weight at late infancy. Pediatrics. 2008;122(suppl 2):S77-S84

41. Li R, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Do infants fed from bottles lack self-regulation of milk intake compared with directly breastfed infants? Pediatrics. 2010;125(6).

42. Rosenbauer J, Herzig P, Giani G. Early infant feeding and risk of type 1 diabetes mellitus—a nationwide population-based case-control study in pre-school children. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(3):211-222

43. Das UN. Breastfeeding prevents type 2 diabetes mellitus: but, how and why? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(5):1436-1437

44. Bener A, Hoffmann GF, Afify Z, Rasul K, Tewfik I. Does prolonged breastfeeding reduce the risk for childhood leukemia and lymphomas? Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60(2):155-161

45. Rudant J, Orsi L, Menegaux F, et al. Childhood acute leukemia, early common infections, and allergy: The ESCALE Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(9):1015-1027

46. Kwan ML, Buffler PA, Abrams B, Kiley VA. Breastfeeding and the risk of childhood leukemia: a meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(6):521-535

47. Der G, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Effect of breast feeding on intelligence in children: prospective study, sibling pairs analysis, and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;333(7575):945-950

48. Kramer MS, Fombonne E, Igumnov S, et al., Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) Study Group. Effects of prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding on child behavior and maternal adjustment: evidence from a large, randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3).

49. Kramer MS, Aboud F, Mironova E, et al., Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) Study Group. Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: new evidence from a large randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):578-584

50. Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, et al., PROBIT Study Group (Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial). Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285(4):413-420

51. Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, et al., NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Beneficial effects of breast milk in the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1).

52. Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, et al., National Institute of Child Health and Human Development National Research Network. Persistent beneficial effects of breast milk ingested in the neonatal intensive care unit on outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants at 30 months of age. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4).

53. Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ. Randomised trial of early diet in preterm babies and later intelligence quotient. BMJ. 1998;317(7171):1481-1487

54. Isaacs EB, Fischl BR, Quinn BT, Chong WK, Gadian DG, Lucas A. Impact of breast milk on intelligence quotient, brain size, and white matter development. Pediatr Res. 2010;67(4):357-362

55. Furman L, Taylor G, Minich N, Hack M. The effect of maternal milk on neonatal morbidity of very low-birth-weight infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(1):66-71

56. Lucas A, Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 1990;336(8730):1519-152

57. Sisk PM, Lovelady CA, Dillard RG, Gruber KJ, O’Shea TM. Early human milk feeding is associated with a lower risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. 2007;27(7):428-43

58. Meinzen-Derr J, Poindexter B, Wrage L, Morrow AL, Stoll B, Donovan EF. Role of human milk in extremely low birth weight infants’ risk of necrotizing enterocolitis or death. J Perinatol. 2009;29(1):57-62

59. Schanler RJ, Shulman RJ, Lau C. Feeding strategies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 pt 1):1150-1157

60. Hintz SR, Kendrick DE, Stoll BJ, et al., NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Neurodevelopmental and growth outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants after necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):696-703

61. Shah DK, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ, et al. Adverse neurodevelopment in preterm infants with postnatal sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis is mediated by white matter abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging at term. J Pediatr. 2008;153(2):170-175, e1

62. Hylander MA, Strobino DM, Dhanireddy R. Human milk feedings and infection among very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/102/3/e38

63. Okamoto T, Shirai M, Kokubo M, et al. Human milk reduces the risk of retinal detachment in extremely low-birthweight infants. Pediatr Int. 2007;49(6):894-897

64. Lucas A. Long-term programming effects of early nutrition—implications for the preterm infant. J Perinatol. 2005;25(suppl 2):S2-S6

65. Singhal A, Cole TJ, Lucas A. Early nutrition in preterm infants and later blood pressure: two cohorts after randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357(9254):413-419

66. Quigley MA, Henderson G, Anthony MY, McGuire W. Formula milk versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD002971

67. Slutzah M, Codipilly CN, Potak D, Clark RM, Schanler RJ. Refrigerator storage of expressed human milk in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2010;156(1):26-28

68. Henderson JJ, Evans SF, Straton JA, Priest SR, Hagan R. Impact of postnatal depression on breastfeeding duration. Birth. 2003;30(3):175-180

69. Strathearn L, Mamun AA, Najman JM, O’Callaghan MJ. Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated child abuse and neglect? A 15-year cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):483-493

70. Krause KM, Lovelady CA, Peterson BL, Chowdhury N, Østbye T. Effect of breast-feeding on weight retention at 3 and 6 months postpartum: data from the North Carolina WIC Programme. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(12):2019-2026

71. Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2005;294(20):2601-2610

72. Schwarz EB, Brown JS, Creasman JM, et al. Lactation and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Am J Med. 2010;123(9):863.e1-e6

73. Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Hankinson SE, Grodstein F. Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3458-3467

74. Schwarz EB, Ray RM, Stuebe AM, et al. Duration of lactation and risk factors for maternal cardiovascular disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):974-982

75. Stuebe AM, Willett WC, Xue F, Michels KB. Lactation and incidence of premenopausal breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1364-1371

76. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):187-195

77. Lipworth L, Bailey LR, Trichopoulos D. History of breast-feeding in relation to breast cancer risk: a review of the epidemiologic literature. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(4):302-312

78. World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: report of an expert consultation. Available at: hwww.who.int/nutrition/publications/optimal_duration_of_exc_bfeeding_report_eng.pdf

79. Institute of Medicine. Early childhood obesity prevention policies. June 23, 2011. Available at: https://ihcw.aap.org/Documents/POPOT/IOM_ObesityPrevention.pdf

80. Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding [review]. The Cochrane Library. January 21, 2009. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003517/full

81. Peterson AE, Peŕez-Escamilla R, Labbok MH, Hight V, von Hertzen H, Van Look P. Multicenter study of the lactational amenorrhea method (LAM) III: effectiveness, duration, and satisfaction with reduced client-provider contact. Contraception. 2000;62(5):221-230

82. Agostoni C, Decsi T, Fewtrell M, et al., ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Complementary feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46(1):99-110

83. Cattaneo A, Williams C, Pallás-Alonso CR, et al. ESPGHAN’s 2008 recommendation for early introduction of complementary foods: how good is the evidence? Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(4):335-343

84. Gonçalves DU, Proietti FA, Ribas JG, et al. Epidemiology, treatment, and prevention of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-associated diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(3):577-589

85. Arroyo Carrera I, López Rodríguez MJ, Sapiña AM, López Lafuente A, Sacristán AR. Probable transmission of brucellosis by breast milk. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52(5):380-381

86. American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:680-701

87. American Academy of Pediatrics. Varicella-zoster infections. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:714-727

88. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009 H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu) and Feeding your Baby: What Parents Should Know. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/infantfeeding.htm?s_cid=h1n1Flu_outbreak_155

89. Horvath T, Madi BC, Iuppa IM, Kennedy GE, Rutherford G, Read JS. Interventions for preventing late postnatal mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;21(1):CD006734

90. Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, Jamieson DJ, et al., BAN Study Group. Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2271-2281

91. Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, et al. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2282-2294

92. Hamele M, Flanagan R, Loomis CA, Stevens T, Fairchok MP. Severe morbidity and mortality with breast milk associated cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(1):84-86

93. Kurath S, Halwachs-Baumann G, Müller W, Resch B. Transmission of cytomegalovirus via breast milk to the prematurely born infant: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(8):1172-1178

94. Maschmann J, Hamprecht K, Weissbrich B, Dietz K, Jahn G, Speer CP. Freeze-thawing of breast milk does not prevent cytomegalovirus transmission to a preterm infant. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91(4):F288-F290

95. Hamprecht K, Maschmann J, Müller D, et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) inactivation in breast milk: reassessment of pasteurization and freeze-thawing. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(4):529-535

96 Jansson LM, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. ABM clinical protocol #21: Guidelines for breastfeeding and the drug-dependent woman. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(4):225-228

97. Garry A, Rigourd V, Amirouche A, Fauroux V, Aubry S, Serreau R. Cannabis and breastfeeding. J Toxicol. 2009;2009:596149

98. Little RE, Anderson KW, Ervin CH, Worthington-Roberts B, Clarren SK. Maternal alcohol use during breast-feeding and infant mental and motor development at one year. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(7):425-430

99. Mennella JA, Pepino MY. Breastfeeding and prolactin levels in lactating women with a family history of alcoholism. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5).

100. Subcommittee on Nutrition During Lactation, Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Nutrition During Lactation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1991:113-152

101. Koren G. Drinking alcohol while breastfeeding. Will it harm my baby? Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:39–41pmid:11852608

102. Guedes HT, Souza LS. Exposure to maternal smoking in the first year of life interferes in breast-feeding protective effect against the onset of respiratory allergy from birth to 5 yr. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20(1):30-34p

103. Liebrechts-Akkerman G, Lao O, Liu F, et al. Postnatal parental smoking: an important risk factor for SIDS. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(10):1281-1291

104. Yilmaz G, Hizli S, Karacan C, Yurdakök K, Coşkun T, Dilmen U. Effect of passive smoking on growth and infection rates of breast-fed and non-breast-fed infants. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(3):352-358

105. Vio F, Salazar G, Infante C. Smoking during pregnancy and lactation and its effects on breast-milk volume. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(6):1011-1016

106. Hopkinson JM, Schanler RJ, Fraley JK, Garza C. Milk production by mothers of premature infants: influence of cigarette smoking. Pediatrics. 1992;90(6):934-938

107. Butte NF. Maternal nutrition during lactation. Pediatric Up-to-Date. 2010. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/maternal-nutrition-during-lactation?source=search_result&search=maternal+nutrition&selectedTitle=2%7E150

108. Zeisel SH. Is maternal diet supplementation beneficial? Optimal development of infant depends on mother’s diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(2):685S-687Sp

109. Picciano MF, McGuire MK. Use of dietary supplements by pregnant and lactating women in North America. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(2):663S-667S

110. Whitelaw A. Historical perspectives: perinatal profiles: Robert McCance and Elsie Widdowson: pioneers in neonatal science. NeoReviews. 2007;8(11):e455-e458

111. Simopoulos AP, Leaf A, Salem N Jr. Workshop on the essentiality of and recommended dietary intakes for omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18(5):487-489

112. Carlson SE. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in pregnancy and lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(2):678S-684S

113. Koletzko B, Cetin I, Brenna JT, Perinatal Lipid Intake Working Group, Child Health Foundation, Diabetic Pregnancy Study Group, European Association of Perinatal Medicine, European Association of Perinatal Medicine, European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Committee on Nutrition, International Federation of Placenta Associations, International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids. Dietary fat intakes for pregnant and lactating women. Br J Nutr. 2007;98(5):873-877

114. Drugs and Lactation Database. 2010. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/

115. Committee on Drugs, American Academy of Pediatrics. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2011, In press

116. Fortinguerra F, Clavenna A, Bonati M. Psychotropic drug use during breastfeeding: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4).

117. REGULATORY GUIDE 8.38 CONTROL OF ACCESS TO HIGH AND VERY HIGH RADIATION AREAS IN NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS

118. International Commission on Radiological Protection. Doses to infants from ingestion of radionuclides in mother’s milk. ICRP Publication 95. Ann ICRP. 2004;34(3-4):1-27

119. Stabin MG, Breitz HB. Breast milk excretion of radiopharmaceuticals: mechanisms, findings, and radiation dosimetry. J Nucl Med. 2000;41(5):863-873

120. Kaplan M, Hammerman C. Severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. A potential complication of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Clin Perinatol. 1998;25(3):575-590, viii

121. World Health Organization. Evidence for the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998

122. World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund. Protecting, Promoting, and Supporting Breastfeeding: The Special Role of Maternity Services. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989

123. Philipp BL, Merewood A, Miller LW, et al. Baby-friendly hospital initiative improves breastfeeding initiation rates in a US hospital setting. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):677-681

124. Murray EK, Ricketts S, Dellaport J. Hospital practices that increase breastfeeding duration: results from a population-based study. Birth. 2007;34(3):202-211

125. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding-related maternity practices at hospitals and birth centers—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(23):621-625

126. Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 pt 1):607-619

127. The Joint Commission: Specifications Manual for Joint Commission National Quality Core Measures.

128. O’Connor NR, Tanabe KO, Siadaty MS, Hauck FR. Pacifiers and breastfeeding: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):378-382

129. Hauck FR, Omojokun OO, Siadaty MS. Do pacifiers reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/116/5/e71

130. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1245-1255

131. Li DK, Willinger M, Petitti DB, Odouli R, Liu L, Hoffman HJ. Use of a dummy (pacifier) during sleep and risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): population based case-control study. BMJ. 2006;332(7532):18-22

132. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Controversies concerning vitamin K and the newborn. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1 pt 1):191-192

133. Wagner CL, Greer FR, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1142-1152

134. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guidelines for Fluoride Therapy, 2018.

135. Garza C, de Onis M. Rationale for developing a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(suppl 1):S5-S14

136. de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, Borghi E. Comparison of the WHO child growth standards and the CDC 2000 growth charts. J Nutr. 2007;137(1):144-148

137. Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0–59 months in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-9):1-15

138. Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NFCenters for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0-59 months in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-9):1-15

139. Schanler RJ. The pediatrician supports breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5(5):235-236

140. Feldman-Winter LB, Schanler RJ, O’Connor KG, Lawrence RA. Pediatricians and the promotion and support of breastfeeding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(12):1142-1149

141. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics Breastfeeding Initiatives. 2010. Available at: http://www.aap.org/breastfeeding

142. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. Clinical Protocols.

143. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):297-316

144. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine and Bright Futures Steering Committee. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1376

145. Cohen R, Mrtek MB, Mrtek RG. Comparison of maternal absenteeism and infant illness rates among breast-feeding and formula-feeding women in two corporations. Am J Health Promot. 1995;10(2):148-153

146. Ortiz J, McGilligan K, Kelly P. Duration of breast milk expression among working mothers enrolled in an employer-sponsored lactation program. Pediatr Nurs. 2004;30(2):111-119

147. Tuttle CR, Slavit WI. Establishing the business case for breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(suppl 1):S59-S62

148. US Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health. Business case for breast feeding. 2010. Available at: www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding/government-in-action/business-case-for-breastfeeding

149. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010, Public Law 111-148. Title IV, §4207, USC HR 3590, (2010

150. Hurst NM, Myatt A, Schanler RJ. Growth and development of a hospital-based lactation program and mother’s own milk bank. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1998;27(5):503-51

151. Schanler RJ, Fraley JK, Lau C, Hurst NM, Horvath L, Rossmann SN. Breastmilk cultures and infection in extremely premature infants. J Perinatol. 2011;31(5):335-338

Pour poser une question, n'utilisez pas l'espace "Commentaires" ci-dessous, envoyez un mail à la boîte contact. Merci